SINKING

By Michail Michailakis

The end

The Britannic departed from Southampton for Moudros at 2.23 p.m. on November 12, 1916. According to Captain Barlett's official report the ship was carrying 1065 people (673 crew, 315 RAMC, 77 Nurses). It would be her sixth voyage in the Mediterranean Sea. She passed Gibraltar around midnight of the 15th and arrived at Naples on the morning of the 17th for her usual coaling and water refueling stop, completing the first stage of her mission. A storm kept the ship at Naples until Sunday afternoon. Then Captain Bartlett decided to take advantage of a brief break in the weather and decided to lift anchors. The seas rose once again just as the Britannic left the port but by next morning the storms died and the ship passed the Strait of Messina without problems. Cape Matapan (the southernmost point of continental Greece) was rounded during the first hours of Tuesday (21 November). By the morning Britannic was steaming at full speed (around 21 knots) into the Kea Channel, between the islands of Makronissos (to her port side) and the island of Kea (to her starboard side).

In the dining room breakfast was served after an early mass held by Rev. John Fleming, one of the ship's chaplains. Among those eating breakfast was stewardess Violet Jessop, one of the two persons onboard who had worked on all three White Star liners. The other one was John Priest, a fireman. At 8.12 a.m. a loud explosion shook the ship. Violet Jessop later recalled:

In the dining room breakfast was served after an early mass held by Rev. John Fleming, one of the ship's chaplains. Among those eating breakfast was stewardess Violet Jessop, one of the two persons onboard who had worked on all three White Star liners. The other one was John Priest, a fireman. At 8.12 a.m. a loud explosion shook the ship. Violet Jessop later recalled:

"Suddenly, there was a dull deafening roar. Britannic gave a shiver, a long drawn out shudder from stem to stern, shaking the crockery on the tables, breaking things till it subsided as she slowly continued on her way. We all knew she had been struck..."

The reaction in the dining room was immediate. Doctors and nurses left instantly for their posts. That seemed strange to Violet Jessop when compared with the calmness aboard Titanic after the collision with the iceberg, but during wartime fear for the worst makes people foresee danger, especially when they are in uniform. However, not everybody reacted in the same way. Further aft the power of the explosion was less felt and many thought the ship had hit a smaller boat. It seems that no casualties occurred as no one was present in the area of the blast, but Private J. Cuthbertson had a close call as the force of the water washed him from G deck up to the E deck through the debris of the staircase located between the two decks. An unknown Britannic Officer (believed to be Fifth Officer Gordon Fielding) was shaving in his cabin after having finished his bath. The explosion threw him with violence across the room with various items falling on top of him. He felt that the ship lifted twice and the fumes from the explosion left him blind for a couple of seconds. After having recovered, he put on some clothes and hurried to his boat station.

On the bridge at the time of the explosion were present Captain Bartlett and Chief Officer Hume. The first reports were alarming and the gravity of the situation became soon evident. The explosion had taken place low on the starboard side between holds 2 and 3, but the force of the explosion had also damaged the watertight bulkhead between hold 1 and the forepeak. That meant that the first 4 watertight compartments were filling rapidly with water. To make things worse, the firemen's tunnel connecting the firemen's quarters in the bow with boiler room 6 had also been seriously damaged and water was flowing into that boiler room. Bartlett ordered the watertight doors closed, sent a distress signal and ordered the crew to prepare the lifeboats. Unfortunately, another bad surprise was waiting. Along with the damaged watertight door of the firemen's tunnel, the watertight door between boiler rooms 6 and 5 also failed to close properly for some unknown reason. Now water was flowing further aft into boiler room 5. The Britannic quickly developed a serious list to starboard.

The Britannic had reached her flooding limit. She could stay afloat (motionless) with six watertight compartments flooded and had five watertight bulkheads raised up to B-deck. Those measures were taken after the Titanic (designed to stay afloat with five watertight compartments flooded) suffered a domino effect with water flowing over the top of the bulkheads, which were not protecting the keel up to B deck but only up to E deck. That meant that the Titanic was NOT really divided into watertight compartments. If we could have called a ship "unsinkable", that would have been the Britannic. According to the reports the crucial bulkhead between boiler rooms 5 and 4 and its door were undamaged and should have guaranteed the survival of the ship. However, there was something else that probably sealed Britannic's fate: the open portholes of the lower decks. Most of these portholes had been opened by the nurses in order to ventilate the wards. As the ship's list increased, water reached their level and began to enter aft from the bulkhead between boiler rooms 5 and 4. With more than six compartments flooded, the Britannic was doomed.

On the bridge, Captain Bartlett was trying to choose the best action in order to save his vessel. Only two minutes after the blast boiler rooms 5 and 6 had to be evacuated. In other words, in about ten minutes the Britannic was roughly in the same condition the Titanic was one hour after the collision with the iceberg. Fifteen minutes after the explosion the open portholes on E deck were underwater. To his right Bartlett saw the shores of Kea, about three miles away. He decided to make a desperate effort to beach the ship. That wasn't an easy task because of the combined effect of the list and the weight of the rudder. The steering gear was unable to respond properly but eventually the Britannic slowly started to turn.

Simultaneously, on the boat deck the crew members were preparing the lifeboats. When the unknown Officer arrived at his boat station (located at the port gantry davits and consisting of 12 lifeboats) he swung out two lifeboats. Those boats were immediately rushed by a group of stewards and some sailors, who had started to panic. The Officer kept his nerve and persuaded his sailors to get out and stand by their positions near the boat stations. He decided to leave the stewards on the lifeboats as they were responsible for starting the panic and he didn't want them in his way during the evacuation. However, he left one of the crew with them in order to take charge of the lifeboat after leaving the ship. After this unfortunate episode all the sailors under his command remained at their posts until the last moment. As no RAMC personnel were near this boat station at that time, the Officer started to lower the boats, but, when he saw that the ship's engines were still running, he stopped them within 6ft from the water and waited for orders from the bridge. The occupants of the lifeboats didn't take this decision very well and started cursing. Shortly after this, orders finally arrived: no lifeboats would be launched, as the Captain had decided to beach the Britannic.

The nurses were grouped and counted into the life boats separately by Matron E. A Dowse, who supervised their evacuation. Assistant Commander Harry William Dyke was making the arrangements for the lowering of the lifeboats from the aft davits of the starboard boat deck when he spotted a group of firemen who had taken a lifeboat from the poop deck without authority and hadn't filled it to its maximum capacity. Dyke ordered them to pick up some of the men who had already jumped into the water. Two lifeboats from the boat station assigned to Third Officer David Laws were lowered without his knowledge through the use of the automatic release gear. Those two lifeboats dropped some 6ft and hit the water violently. Violet Jessop was one of their unlucky occupants. In her memoirs she remembered that:

On the bridge, Captain Bartlett was trying to choose the best action in order to save his vessel. Only two minutes after the blast boiler rooms 5 and 6 had to be evacuated. In other words, in about ten minutes the Britannic was roughly in the same condition the Titanic was one hour after the collision with the iceberg. Fifteen minutes after the explosion the open portholes on E deck were underwater. To his right Bartlett saw the shores of Kea, about three miles away. He decided to make a desperate effort to beach the ship. That wasn't an easy task because of the combined effect of the list and the weight of the rudder. The steering gear was unable to respond properly but eventually the Britannic slowly started to turn.

Simultaneously, on the boat deck the crew members were preparing the lifeboats. When the unknown Officer arrived at his boat station (located at the port gantry davits and consisting of 12 lifeboats) he swung out two lifeboats. Those boats were immediately rushed by a group of stewards and some sailors, who had started to panic. The Officer kept his nerve and persuaded his sailors to get out and stand by their positions near the boat stations. He decided to leave the stewards on the lifeboats as they were responsible for starting the panic and he didn't want them in his way during the evacuation. However, he left one of the crew with them in order to take charge of the lifeboat after leaving the ship. After this unfortunate episode all the sailors under his command remained at their posts until the last moment. As no RAMC personnel were near this boat station at that time, the Officer started to lower the boats, but, when he saw that the ship's engines were still running, he stopped them within 6ft from the water and waited for orders from the bridge. The occupants of the lifeboats didn't take this decision very well and started cursing. Shortly after this, orders finally arrived: no lifeboats would be launched, as the Captain had decided to beach the Britannic.

The nurses were grouped and counted into the life boats separately by Matron E. A Dowse, who supervised their evacuation. Assistant Commander Harry William Dyke was making the arrangements for the lowering of the lifeboats from the aft davits of the starboard boat deck when he spotted a group of firemen who had taken a lifeboat from the poop deck without authority and hadn't filled it to its maximum capacity. Dyke ordered them to pick up some of the men who had already jumped into the water. Two lifeboats from the boat station assigned to Third Officer David Laws were lowered without his knowledge through the use of the automatic release gear. Those two lifeboats dropped some 6ft and hit the water violently. Violet Jessop was one of their unlucky occupants. In her memoirs she remembered that:

"...the lifeboat started gliding down rapidly, scraping the ship's side, splintering the glass in our faces from the boxes, which formed, when lighted, the green lighted band around a hospital ship's middle, and making a terrible impact as we landed on the water..."

The two lifeboats soon drifted into the giant running propellers, which were almost out of the water by now. As the first one reached the turning blades, the tragedy of the day took place. The spectacle was horrifying and beyond imagination. Violet Jessop described the scene in a very vivid way:

"...eyes were looking with unexpected horror at the debris and the red streaks all over the water. The falls of the lowered lifeboat, left hanging, could now be seen with human beings clinging to them, like flies on flypaper, holding on for dear life, with a growing fear of the certain death that awaited them if they let go...."

Moments after touching the water, her lifeboat (No.4) clustered with the other lifeboats already in the water, struggling to get free from the ship's side, but it was rapidly drifting into the propellers. She wrote:

"...every man jack in the group of surrounding boats took a flying leap into the sea. They came thudding from behind and all around me, taking to the water like a vast army of rats.[.....]I turned around to see the reason for this exodus and, to my horror, saw Britannic's huge propellers churning and mincing up everything near them-men, boats and everything were just one ghastly whirl."

Although she couldn't swim she overcame her fear in front of the danger and jumped into the water.....One of the people who jumped with her was George Perman, one of the sea-scouts serving on the Britannic. At the last moment he was able to grab a davit cable and escaped death. Violet Jessop's lifebelt brought her to the surface, where she violently hit her head twice on something solid. Suddenly, she grabbed an arm but having heard that people drowning retain their hold after death, she let go. After some more agonizing seconds she finally reached the surface with her clothes almost torn off her. Then she opened her eyes:

"...The first thing my smarting eyes beheld was a head near me, a head split open, like a sheep's head served by the butcher, the poor brains trickling over on to the khaki shoulders. All around were heart-breaking scenes of agony, poor limbs wrenched out as if some giant had torn them in his rage. The dead floated by so peacefully now, men coming up only to go down again for the last time, a look of frightful horror on their faces..."

She closed her eyes to keep out the scene while trying to keep her nose out of the water (the lifebelts used at the time couldn't support the weight of the head and this sometimes was fatal for people who were unconscious or who couldn't swim).

Unaware of the massacre, Captain Bartlett had observed that the water was entering more rapidly as Britannic was moving forward and gave the order to stop the engines. The propellers stopped turning the moment a third lifeboat was about to be reduced to pieces. Captain T. Fearnhead and some other RAMC occupants of this boat pushed against the blades and got away from them safely.

Unaware of the massacre, Captain Bartlett had observed that the water was entering more rapidly as Britannic was moving forward and gave the order to stop the engines. The propellers stopped turning the moment a third lifeboat was about to be reduced to pieces. Captain T. Fearnhead and some other RAMC occupants of this boat pushed against the blades and got away from them safely.

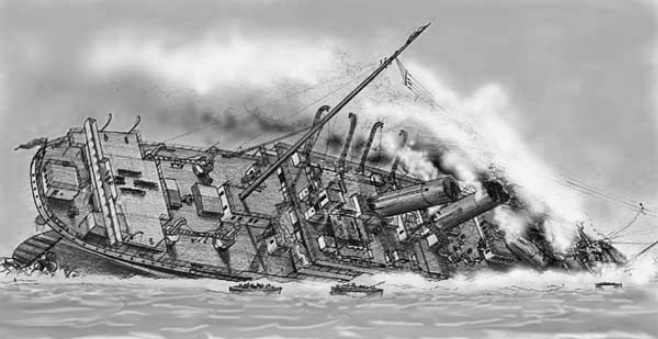

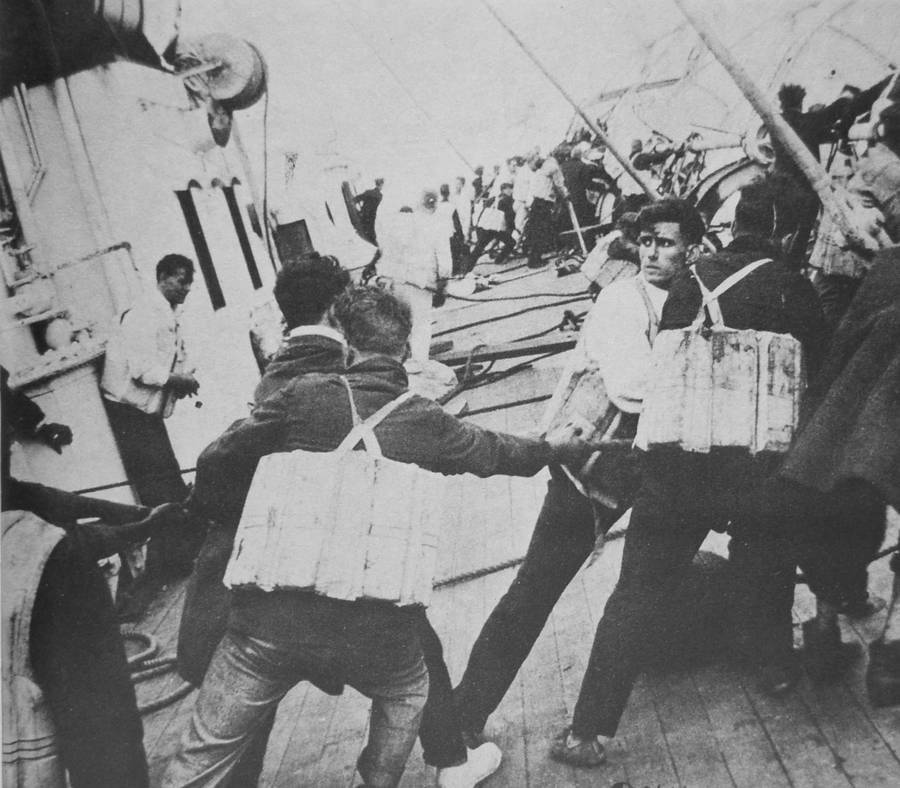

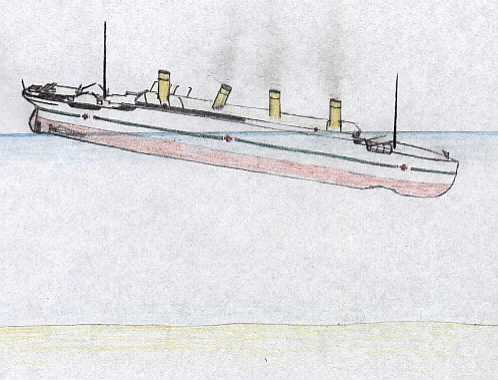

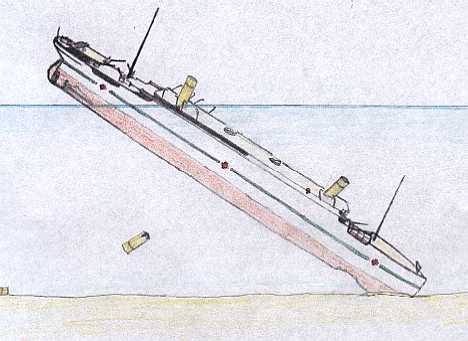

A dramatic image captured during the sinking of the SS VESTRIS (November 12, 1928) by crew member Fred Hanson. Similar scenes took place aboard the BRITANNIC, as her list continued to increase. The ropes used to access the lifeboats at the port side are still visible on the boat deck of the sunken White Star liner.

The Captain ordered the crew to lower the boats and at 8:35 a.m. he gave the order to abandon ship. The forward set of port side davits soon became useless. The unknown Officer had already launched his two lifeboats and also managed to launch rapidly one more boat from the after set of port side davits. He then started to prepare the motor launch when First Officer Oliver came with orders from the Captain. Bartlett had ordered Oliver to get in the motor launch and use her speed to pick up survivors from the smashed lifeboats. Then he was to take charge of the small fleet of lifeboats formed around the doomed liner. After launching the motor launch with Oliver, the unknown Officer filled another lifeboat with 75 men and launched it with great difficulty due to the list to starboard. At 8:45 a.m. the list was so great that no davits were operable. The unknown Officer with six sailors decided to to throw overboard collapsible rafts and deck chairs from the starboard side. They were followed by about 30 RAMC ratings who were still left on the ship. As he was about to order these men to jump and then give his final report to the Captain, the unknown Officer spotted Sixth Officer Welch and a few sailors near one of the smaller lifeboats on the starboard side. They were trying to lift the boat but they hadn't enough men. Quickly, the unknown Officer ordered his group of 40 men to assist the Sixth Officer. Together they managed to lift it , load it with men and then launch it safely. Around 8:50a.m. Bartlett noticed that the rate of the flooding had decreased while the ship was not moving and restarted the engines in a second attempt to beach his command. However he aborted as soon as water was reported on D-Deck.

At 9:00 a.m. Bartlett sounded one last blast on the whistle and then just walked into the water, which had already reached the bridge. He swam to a collapsible boat and began to co-ordinate the rescue operations. The whistle blow was the final signal for the ship's engineers (commanded by Chief Engineer Robert Fleming) who, like their heroic colleagues on the Titanic, had remained at their posts until the last possible moment. They escaped via the staircase into funnel #4 which was serving to ventilate the engine room. The Assistant Chief Engineer was seen sliding over the stern. After a fall of about 150ft he managed to avoid the floating wreckage and he was picked up by the lifeboat of the unknown Officer. Then the Britannic rolled over her starboard side and the funnels began collapsing and the deck machinery fell into the water as the ship vanished into the depths. It was 9:07 a.m., only 55 minutes after the explosion. In total, 28 lifeboats had been lowered into the water.

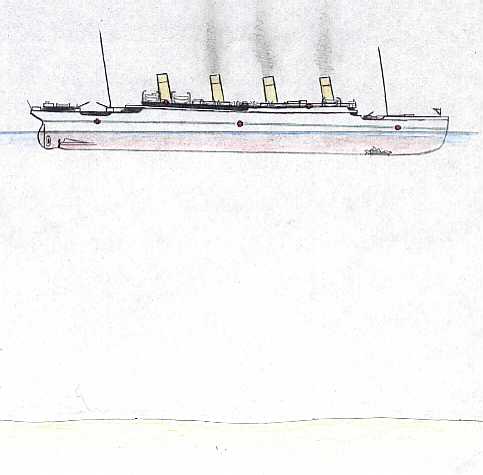

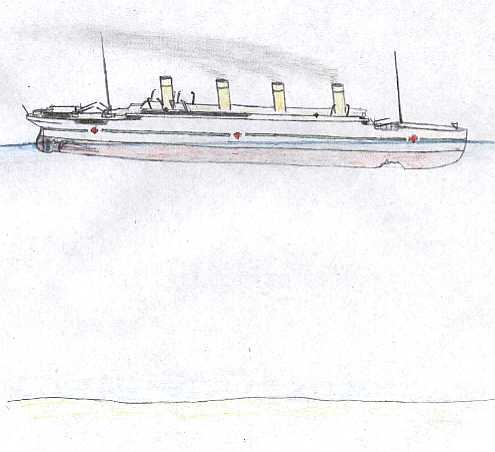

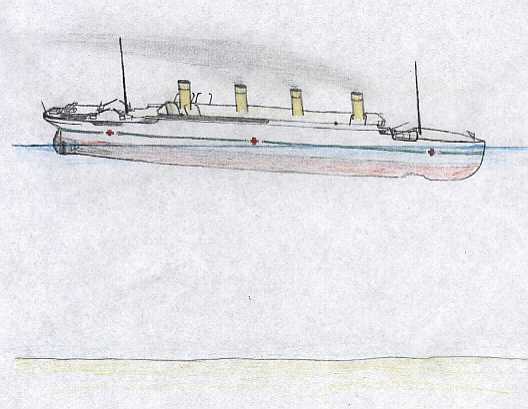

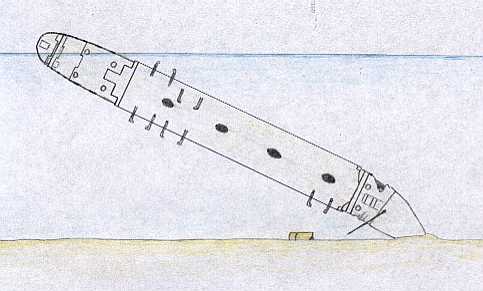

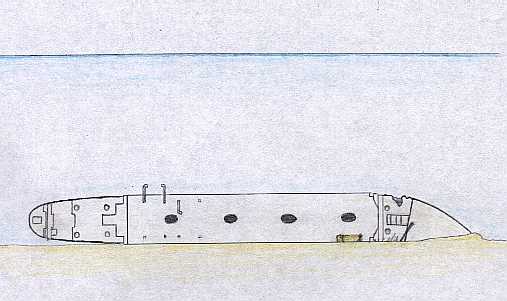

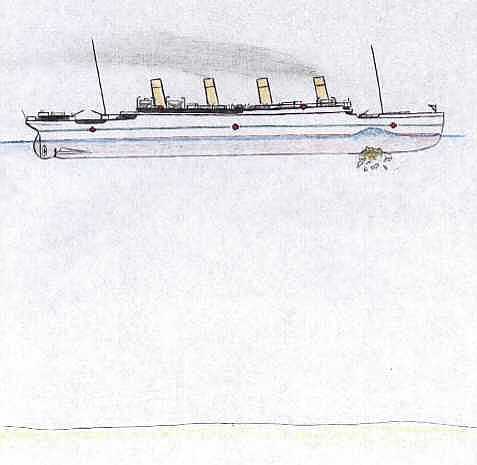

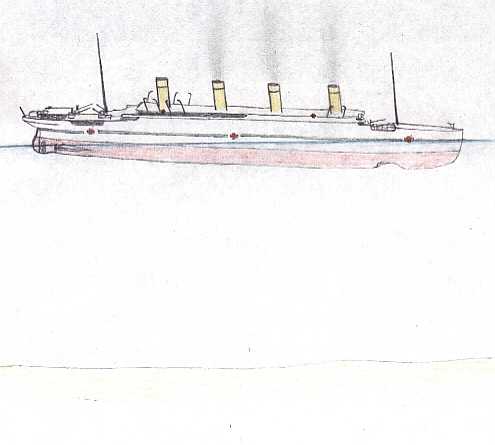

Illustrated timeline of the sinking (© 2003 Remco Hillen)

08:12 The BRITANNIC is thrown instantly off-course by three points (33.75 degrees), while her bow rises noticeably and then falls back down. Severe shaking and vibrations along the hull. The engines are stopped and the lifeboats are made ready to be lowered. After less than 2 minutes Boiler Room 6 is already flooded and inoperable. Advancing flooding into Boiler Room 5. The water is about 180m/591ft deep.

08:35 Bartlett decides to stop the ship and orders all boats to be sent away. He's unaware that just minutes before his order two lifeboats have been drawn into the portside propeller (killing most of their occupants), while a third one has a narrow escape as the propeller stops seconds before impact.

09:00 When Bartlett is informed of the water on D-Deck he gives the order to abandon ship and BRITANNIC's whistle is blown for the last time. Water has by now reached the bridge and Assistant Commander Dyke informs his Captain that all have left the ship. Dyke, Chief Engineer Fleming and Bartlett simply walk into the sea near the forward gantry davits. Shortly after their escape funnel No.3 collapses.

09:04 The water is now 119m/390ft deep and BRITANNIC's bow hits the bottom whilst the stern is still above the surface. The last few men who were below decks -so not seen by Assistant Commander Dyke- have by now left the ship. Fifth Officer Fielding estimates the stern rising some 46m/150 feet into the air.