AFTERMATH

By Michail Michailakis

At 8:15 a.m. the British destroyer Scourge received the distress signal sent by the ill-fated hospital ship. Immediately, her Captain set course for the Kea channel and also ordered the French tugs Goliath and Polyphemus to follow. At 8:28 a.m the auxiliary cruiser Heroic, which had encountered the Britannic earlier that day, received the signal and reversed course immediately. At 8:35 a.m. the Scourge requested the assistance of another British destroyer, the Foxhound, which was on patrol in the Gulf of Athens.

Northwest of port St. Nicolo (modern Korissia) on Kea, the calm waters were full of debris, lifeboats, corpses and survivors. The crew had managed to get into the water 35 of 58 lifeboats in less than 50 minutes. Luckily, at least one of the ship's innovations proved to be crucial for the rescue of the hundreds of people who were scattered all over the area of the disaster. Within moments the two motor launches rapidly picked up many survivors as they were much faster than the non-motored lifeboats and were also much easier to operate. The first to arrive on the scene were the Greek fishermen from Kea on their kaikia (small fishing boats), who picked up many men from the water. One of them, Francesco Psilas, was later paid £4 by the Admiralty for his services. At 10:00 a.m. the Scourge sighted the first lifeboats and ten minutes later stopped and picked up 339 survivors. The Heroic had arrived some minutes earlier and picked up 494. Some 150 had made it to port St. Nicolo, where surviving doctors and nurses from the Britannic were trying to save the horribly mutilated men using aprons and pieces of lifebelts to make dressings. A little barren quayside served as their operating room. Although the motor launches were quick to transport the wounded to Korissia, the first lifeboat arrived there some two hours later due to the strong current and their heavy load. It was the lifeboat of Sixth Officer Welch and the unknown Officer. The latter was able to speak some French and managed to talk with one of the local villagers, obtaining some bottles of brandy and some bread for the injured. The inhabitants of Korissia were deeply moved by the suffering of the wounded.

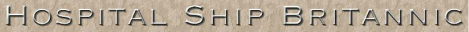

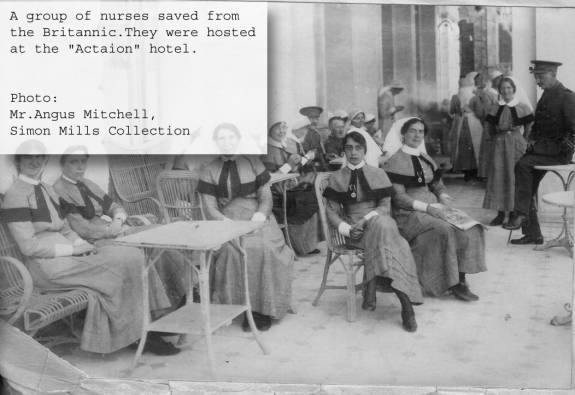

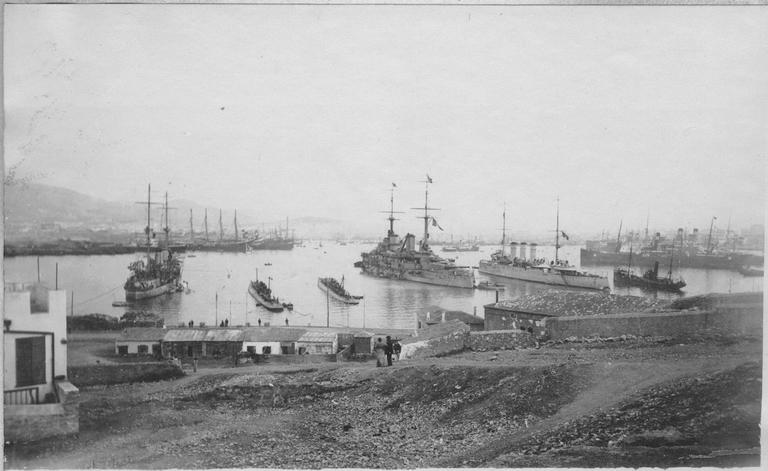

The Scourge and the Heroic had no deck space for more survivors and they left for Pireaus signaling the presence of those left at Korissia. Luckily, the Foxhound arrived at 11.45 a.m. and, after sweeping the area, anchored in the small port at 1:00 p.m. to offer medical assistance and take onboard the remaining survivors. At 2:00 p.m. arrived the light cruiser Foresight. The Foxhound departed for Pireaus at 2:15 p.m. while the Foresight remained to arrange the burial on Kea of Sergeant W. Sharpe, who had died of his injuries. In total, 1035 people were saved. The casualties were 30 men (21 crew, 9 RAMC) and 38 injured (18 crew, 20 RAMC). Two men died on the Heroic and one on the French tug Goliath. The three were buried with military honors in the British cemetery at Pireaus on November 22, 1916. The last fatality was G. Honeycott, who died at the Russian Hospital of Pireaus shortly after the funerals and he was buried near the others. The survivors found shelter on various ships of the Anglo-French fleet that was anchored off the port of Pireaus. The fleet was imposing a naval embargo after the failure of the Allies to have military supplies and ships handed to them by the Greeks and the fierce battle that followed in downtown Athens between the Allied forces and some reservists of the Greek Army, just days before the arrival of the Britannic surviors. The nurses and the medical officers stayed in different hotels at Phaleron.

The medical officers received a hostile reception from the Greek royalists but the nurses were seen as exotic creatures when they ventured in downtown Athens for shopping and sight-seeing. The Athenian newspaper EMPROS [Forward] even dedicated to them the following first-page collumn on November 25, 1916 [November 12, 1916 in the Julian calendar, then followed by Greece]:

ENGLISH WOMEN

I don’t believe that there is another race on the globe whose most beautiful half includes such wild contradictions, as that of Britain's female population. It includes angels and monsters. Beauties that have come to life from Pre-Raphaelitic dramas, Boticelli paintings, but also unprecedented mistakes of Nature, uglinesses so flamboyant and incredible that one would think that they are not creatures of the good God but creations of a malicious imagination, something artificial and out of this world. The British are perfect even in ugliness.

Our fellow citizens had the chance to make this casual observation not in the fog of London but on the sidewalks of Athens, where the BRITANNIC caused harm to her genteel cargo of nurses. Flooding Stadiou Str. with the charming tweets of British utterances, pronounced between clenched teeth and larynx, with a slightly interrogative tone. This herd passes by, buying postcards of the eternal Parthenon, eating bananas on foot and above all, offering itself as a spectacle to the passers-by with that monumental English simplicity which can’t be bothered by anything and is unconcerned of what others might say.

Well, it is within this attractive caravan that one can see little peachy-red faces; like the apples and peaches from Mount Pilio. Their description would require the pen of Theophilus Gautier, who knew two hundred similes for white and three hundred for peach. Lucid eyes like those of an infant, and above all sound bodies. Builds wiry, but full of the juices of life; with the gentle curves of a tall, lean Arabic mare. The best compliment paid to one of these fresh creatures was made by a young shoe shiner, who cried, “Jesus! She looks like the tea advertisement!”.

The white headband, whose extremities were flapping in the autumn morning wind, the elegant grey-blue linen apron, the small cape, the red stripes and the cross on the armband, indeed made the young girl appear to be the trademark beauty of Red Cross Tea. She was a masterpiece for which the Lord should have been awarded with the Medal of Artistic Merit.

But what "thing"? What kind of animal, terror, or ghoul was the one that followed? People were fleeing as if they had seen a goblin. Imagine a wooden spit, like the ones we use for the lamb during Easter, a spit from which women’s clothing idly hang, crying over their fate. Then picture another plank of wood, forming a cross, which represents the shoulders and on top of that, a head with a face as red as a roof tile; long and flat, with a droopy nose. A jaw moving up and down and a mouth that seemed to have been torn by a butcher’s clever. Wrinkles as deep as canyons to the right and left of it. The face of a Quartermaster wearing an old lady’s theater wig made of eelgrass. A hand that could leave a dragoon breathless with the first slap and a voice of a baritone- husky, cavernous, frightening. The voice of a drunk coachman.

[The people on] Stadiou Str. mind-boggled. A practical fellow citizen pulled me aside in order to ask me the following, “Did you see her? Am I to blame when I say that they don’t have politicians? If Asquith had her sent to the front and placed at Picardy, wouldn’t the Germans flee in fright? But they have no brain!”.

SIgned FORTUNIO

[Real Name: Spyros Melas (1882 - 1966), famous Greek collumnist, play-writer, actor, director. Elected President of the Academy of Athens in 1959.]

[Many thanks to Lea Kouvarakou for the Engish adaptation]

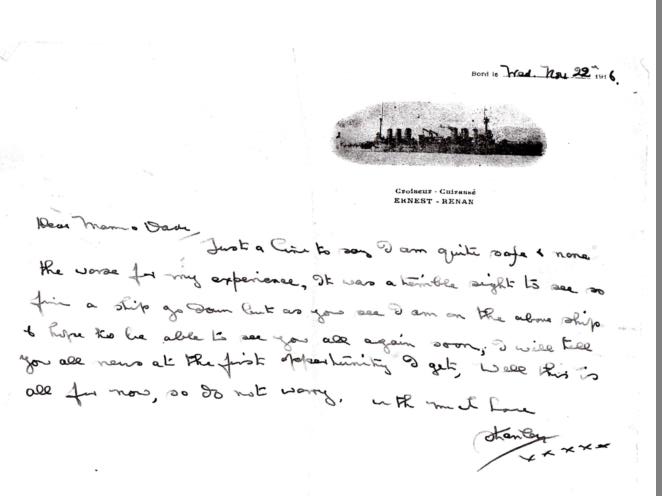

A letter written by an unidentified Britannic survivor hosted onboard the French battle cruiser ERNEST RENAN after his rescue: "Dear Mom & Dad, just a line to say I am quite safe and none the worse for my experience. It was a terrible sight to see so fine a ship go down. As you see I am on the above ship. I hope to be able to see you all again soon. I will tell you all the news at the first opportunity I get. Well this is all for now, so do not worry. With much Love, Stanley." (John Thompson Collection)

The investigation regarding the loss of the Britannic was conducted on the British flagship Duncan by Captain Hugh Heard (Commanding Officer) and Commander George Staer (Chief Engineer). The problems were many, as most of the survivors were scattered around the ships of the Allied fleet and some of their accounts were contradictory. Despite the difficulties the two officers concluded their investigation on November 24, 1916 and prepared a thin 726-word document and three simple sketches of the damaged areas of the Britannic. The report was mainly a summary of the event and failed to present convincing evidence regarding the cause of the explosion (mine or torpedo). The final sentence was "The probability seems to be a mine". Additional reports were later submitted by Captain Charles A. Bartlett (Captain of the Britannic), who wrote that "...a mine might have been the cause, but there is good evidence that the tracks of two torpedoes were seen...", and by Lieut.Col Henry S. Anderson (Commander of the RAMC troops on the Britannic), who wrote a very detailed list of the actions performed by many of his men during the sinking.

The RAMC officers of the Britannic and the uninjured crew members started the long journey home on the RFA Ermine. The ship left Pireaus (Nov. 24) escorted by the Foxhound, and arrived at Salonika the following morning. The men had to wait another day in order to be transferred aboard the Lord Nelson, where they finally managed to take a bath and then to eat a decent meal. Then they went aboard the transport Royal George. The transport left Salonika the following afternoon for a five-day journey to Marsailles. During the trip many men suffered from dysentery. When the ship arrived in France on Saturday (Dec.2) Captain Bartlett took a scheduled overland train for England while the rest of the men had to wait until Monday in order to get their train. The fifty-hour journey was terrible as the carriages were not heated and food was scarse. Some men managed to buy some bread and cheese from some stations but the situation soon became desperate. On December 6th, the train finally arrived at the station of Le Havre, from where the men walked for five miles in order to arrive to their Rest Camp in order to pass the night. The next morning there was no breakfast and they had to wait until 03.00 p.m. for the meal. One hour later, they departed for a six-mile walk to the docks, where they embarked on the trasport Caesarea. Their nightmare ended at 09.00 a.m. of December 8th, when the ship finally arrived to Southampton. Captain Bartlett was on the quay to welcome them and each man was granted a survivor's leave of two weeks.

The medical staff and the wounded survivors remained in Athens until November 27th. Then they were taken aboard the HMHS Grantully Castle and departed for Malta, where they arrived on November 30th. The group stayed there for seventeen days and there was much time to relax before finding a vessel for their return to England, the HMHS Valdivia. The voyage was very difficult because the ship was rolling too much and there were not sufficient supplies of fresh water. The situation became more critical when arrived the order to close all the portholes on the lower decks. The hospital ship finally docked at Southampton on Boxing Day. This was the final chapter of the story of the third Olympic-class liner.

Most of the Britannic victims were left in the water and their memory is honored in memorials in England and Greece. The names of the RAMC men can be found at the Mikra Memorial (Salonika) and those of the crew at the Tower Hill Memorial (London). The four Britannic graves at Pireaus can still be found at the Naval and Consular Cemetery, now located inside the big Municipal Cemetery of Drapetsona. The location of the grave of RAMC Sergeant William Sharpe remained unknown for almost 90 years but the enigma was solved in 2006, when research by Michail Michailakis and Simon Mills managed to establish that he is currently buried at the New British Cemetery on the island of Syros.

The RAMC officers of the Britannic and the uninjured crew members started the long journey home on the RFA Ermine. The ship left Pireaus (Nov. 24) escorted by the Foxhound, and arrived at Salonika the following morning. The men had to wait another day in order to be transferred aboard the Lord Nelson, where they finally managed to take a bath and then to eat a decent meal. Then they went aboard the transport Royal George. The transport left Salonika the following afternoon for a five-day journey to Marsailles. During the trip many men suffered from dysentery. When the ship arrived in France on Saturday (Dec.2) Captain Bartlett took a scheduled overland train for England while the rest of the men had to wait until Monday in order to get their train. The fifty-hour journey was terrible as the carriages were not heated and food was scarse. Some men managed to buy some bread and cheese from some stations but the situation soon became desperate. On December 6th, the train finally arrived at the station of Le Havre, from where the men walked for five miles in order to arrive to their Rest Camp in order to pass the night. The next morning there was no breakfast and they had to wait until 03.00 p.m. for the meal. One hour later, they departed for a six-mile walk to the docks, where they embarked on the trasport Caesarea. Their nightmare ended at 09.00 a.m. of December 8th, when the ship finally arrived to Southampton. Captain Bartlett was on the quay to welcome them and each man was granted a survivor's leave of two weeks.

The medical staff and the wounded survivors remained in Athens until November 27th. Then they were taken aboard the HMHS Grantully Castle and departed for Malta, where they arrived on November 30th. The group stayed there for seventeen days and there was much time to relax before finding a vessel for their return to England, the HMHS Valdivia. The voyage was very difficult because the ship was rolling too much and there were not sufficient supplies of fresh water. The situation became more critical when arrived the order to close all the portholes on the lower decks. The hospital ship finally docked at Southampton on Boxing Day. This was the final chapter of the story of the third Olympic-class liner.

Most of the Britannic victims were left in the water and their memory is honored in memorials in England and Greece. The names of the RAMC men can be found at the Mikra Memorial (Salonika) and those of the crew at the Tower Hill Memorial (London). The four Britannic graves at Pireaus can still be found at the Naval and Consular Cemetery, now located inside the big Municipal Cemetery of Drapetsona. The location of the grave of RAMC Sergeant William Sharpe remained unknown for almost 90 years but the enigma was solved in 2006, when research by Michail Michailakis and Simon Mills managed to establish that he is currently buried at the New British Cemetery on the island of Syros.